Golang Tutorial For Beginners a Guide

Welcome to the world of Go, often known as Golang, a programming language that emphasises ease of use, simplicity, and efficiency. This Golang course is designed for all skill levels, from experienced developers learning a new language to total beginners venturing into the world of programming. We will walk you through the foundations of Go in this extensive tutorial, offering you practical advice, step-by-step explanations, and real-world examples to help you develop a solid Golang foundation.

Google engineers developed Go to solve frequent problems that developers encountered when working on large-scale software development projects. Go is becoming more and more popular across a range of industries, including web development, system programming, and cloud computing. It is well-known for its clear syntax, strong concurrency support, and simple compilation.

What is Golang tutorial for beginners

We will begin this course by teaching you to the fundamental ideas of Golang. Each part aims to progressively deepen your comprehension of the language, covering topics like as configuring your development environment and comprehending data types, control structures, functions, and more. As we move along, we’ll cover more complex subjects like goroutines, channels, and error handling, giving you the tools you need to fully use Move’s capabilities to create scalable and effective applications.

This course is your key to learning the fundamentals of Golang, whether your goal is to become a skilled Go developer or you just want to learn more about programming. Together, we will explore the world of Go and acquire the knowledge and abilities required to develop reliable, high-performing applications.

How to Install Golang

You’ve decided to explore the world of Go (or Golang) and set out to become an expert coder. Fantastic decision! However, you must first set up your development environment before you can begin writing your first Go programme. We’ll walk you through the whole Go installation process in this video, making sure you have everything you need to start your Golang journey.

Installing Go on Windows

Step 1: Download the Installer

Visit the official Go website (https://golang.org/dl/) to download the latest stable release for Windows. Choose the MSI installer suitable for your architecture (32-bit or 64-bit).

Step 2: Run the Installer

Once the installer is downloaded, double-click on the file to initiate the installation process. Follow the on-screen instructions to complete the installation. By default, Go will be installed in the C:\Go directory.

Step 3: Verify the Installation

Open a command prompt and type the following command:

go version

If Go is installed correctly, you should see information about the installed version.

Installing Go on macOS

Step 1: Download the Package

On macOS, you can use Homebrew or download the package directly from the official Go website. For the direct download method, visit https://golang.org/dl/ and choose the macOS package suitable for your system.

Step 2: Run the Installer

Double-click on the downloaded package file and follow the installation instructions. By default, Go will be installed in the /usr/local/go directory.

Step 3: Verify the Installation

Open a terminal and type the following command:

go version

If Go is installed correctly, you should see information about the installed version.

Installing Go on Linux

Step 1: Download the Archive

On Linux, you can download the Go archive and extract it to your preferred location. Visit https://golang.org/dl/ and choose the Linux package suitable for your architecture.

Step 2: Extract the Archive

Open a terminal and run the following commands to extract the archive:

tar -C /usr/local -xzf go$VERSION.$OS-$ARCH.tar.gz

Step 3: Set Path Variables

Add the Go binary directory to your PATH environment variable. Edit your shell profile file (e.g., .bashrc or .zshrc) and add the following lines:

export PATH=$PATH:/usr/local/go/bin

export GOPATH=$HOME/go

Save the file and run:

source ~/.bashrc

Step 4: Verify the Installation

Run the following command in the terminal:

go version

If Go is installed correctly, you should see information about the installed version.

Congratulations! You’ve successfully installed Go on your machine. With your development environment set up, you’re now ready to explore the basics of Go programming in our next tutorial. Happy coding!

Setting Up Visual Studio Code for Golang

Having a strong and effective Integrated Development Environment (IDE) will greatly improve your coding experience as you dive deeper into the realm of Go programming. Go programming is easily supported by the well-liked and adaptable code editor Visual Studio Code (VSCode). We’ll walk you through configuring VSCode for Golang in this article so you have the resources you need to optimise your development process.

Why Use Visual Studio Code for Go?

Visual Studio Code is a great option for Go programming because of its reputation for being feature-rich but lightweight. Both novice and seasoned developers will find VSCode to be a pleasant environment because to its abundance of extensions and user-friendly UI. You may take use of features like intelligent code completion, an integrated terminal, and robust debugging capabilities by setting up VSCode for Go.

Step 1: Install Visual Studio Code

If you haven’t already installed VSCode, you can download it from the official website: Visual Studio Code. Follow the installation instructions specific to your operating system.

Step 2: Install the Go Extension

- Open VSCode and navigate to the Extensions view by clicking on the Extensions icon in the Activity Bar on the side of the window or by using the shortcut

Ctrl + Shift + X. - Search for “Go” in the Extensions view search box.

- Install the “Go” extension provided by the Go Team at Google.

- Once the installation is complete, you may need to reload VSCode to activate the extension.

Step 3: Configure Your Workspace

- Open your Go project folder or create a new one.

- Create a new file named go.mod in the root of your project. This file will manage your project’s dependencies.

- Open a terminal within VSCode (

Ctrl +), navigate to your project folder, and run:

go mod init example.com/myproject

Replace example.com/myproject with your project’s import path.

Step 4: Configure Go Tools

- Open the VSCode settings by clicking on the gear icon in the bottom left corner and selecting “Settings.”

- Click on the “Extensions” tab on the left sidebar.

- Scroll down and find the “Go” section. You can customize various settings here, such as formatting options and workspace-specific configurations.

Step 5: Install Additional Tools (Optional)

The Go extension for VSCode comes with built-in support for many Go tools. However, you might want to install additional tools for specific tasks. Open a terminal within VSCode and install the desired tools using the [go get](https://withcodeexample.com/a-comprehensive-guide-to-installing-packages-using-go-get) command. For example:

go get -u golang.org/x/tools/cmd/guru

go get -u github.com/mdempsky/gocode

Step 6: Start Coding!

With Visual Studio Code setup for Go, you’re now ready to start coding. Launch your Go files, take use of the Go extension’s robust capabilities, and experience intelligent code completion. VSCode will make your Golang development experience easy and fun by helping you with formatting, error checking, and code navigation.

Best wishes! You’ve successfully configured Visual Studio Code to work with Go code. Now, use your new coding environment by diving into our Golang lesson for beginners! Have fun with coding!

Hello, World Program in Golang

- Open your favorite text editor or integrated development environment (IDE).

- Create a new file with a

.goextension, for example,hello.go.

Now, let’s write the “Hello, World!” program in Go:

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

fmt.Println("Hello, World!")

}

Explanation:

package main: Every Go program starts with a package declaration. Themainpackage is special—it indicates that this is the entry point of the program.import "fmt": This line imports thefmtpackage, which provides functions for formatting and printing output.func main() { ... }: Themainfunction is the entry point of the program. When you run a Go program, it automatically starts executing from themainfunction.fmt.Println("Hello, World!"): This line prints the “Hello, World!” message to the console. ThePrintlnfunction from thefmtpackage is used to print a line of text followed by a newline.

Once you’ve written the program, save the file. Now, you can run it using the following steps:

- Open a terminal or command prompt.

- Navigate to the directory where you saved the

hello.gofile. - Run the following command:

go run hello.go

You should see the output:

Hello, World!

Congratulations! You’ve just written and executed your first Go program. This simple “Hello, World!” example is a great starting point for exploring more complex features and concepts in the Go programming language.

Golang workspace

The way that Go handles code and dependencies is based on the idea of a workspace. In essence, a Go workspace is a directory structure that complies with certain standards required by the Go tools. The workspace contains three primary directories: src, pkg, and bin.

Here’s a breakdown of each directory in a typical Go workspace:

- src (source): This is where your Go source code resides. Each Go project should be organized as a separate directory under

src. For example, if your project is hosted on GitHub atgithub.com/yourusername/yourproject, your project structure should mirror this URL, with the root of your project located atsrc/github.com/yourusername/yourproject. - pkg (package): This directory holds compiled package objects. When you build a Go program, the compiled packages are stored here. It is also divided based on the architecture and operating system. For instance,

pkg/linux_amd64will contain packages compiled for 64-bit Linux systems. - bin (binary): The

bindirectory stores executable binaries after compilation. As withpkg, it is also divided based on the architecture and operating system.

When working with Go, it’s common to have a single workspace for all your Go projects. This is because Go expects to find your code in a specific location within the workspace.

Setting Up a Go Workspace:

- Create a Workspace Directory:

bash mkdir ~/go

2. Set GOPATH Environment Variable:

Add the following line to your shell profile file (e.g.,.bashrc,.zshrc):bash export GOPATH=~/go export PATH=$PATH:$GOPATH/bin

Then, run:

source ~/.bashrc # or source ~/.zshrc for zsh

- Organize Your Project:

Create a directory for your Go project inside thesrcdirectory. For example:

mkdir -p ~/go/src/github.com/yourusername/yourproject

Place your Go source files in this directory.

- Build and Run:

You can build and run your Go programs from anywhere on your system. For example:

go install github.com/yourusername/yourproject

The executable will be in ~/go/bin/yourproject.

You may help the Go tools handle your code and dependencies more efficiently by adhering to certain rules. It’s crucial to note that you may operate outside of the GOPATH with Go modules, which were introduced in Go 1.11. This relaxes the requirement for a tight GOPATH. Still, knowing the GOPATH structure is helpful, particularly when collaborating on already-existing codebases or working on older projects.

Variables in Golang

Variables are used in Go to organise and store data. The var keyword is used to construct them, and the compiler can either automatically deduce their type or define them explicitly. Here are some instances of variables declared and used in Go:

Example 1: Implicit Type Declaration

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Implicit type declaration

var message = "Hello, Go!"

fmt.Println(message)

}

In this example, the type of the variable message is implicitly inferred from the assigned value, which is a string.

Example 2: Explicit Type Declaration

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Explicit type declaration

var age int

age = 25

fmt.Println("Age:", age)

}

Here, we declare a variable age with an explicit type of int. We later assign a value of 25 to it and print the result.

Example 3: Short Variable Declaration

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Short variable declaration

name := "John"

fmt.Println("Name:", name)

}

The short variable declaration := is a concise way to declare and initialize a variable. The type is inferred from the assigned value.

Example 4: Multiple Variables

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Multiple variables

var (

firstName = "Alice"

lastName = "Smith"

age = 30

)

fmt.Printf("Name: %s %s, Age: %d\n", firstName, lastName, age)

}

You can declare multiple variables at once using the var keyword with parentheses.

Example 5: Constants

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Constants

const pi = 3.14159

fmt.Println("Value of pi:", pi)

}

Constants are declared using the const keyword. They must be assigned a value at the time of declaration and cannot be changed later.

Example 6: Zero Values

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Zero values

var zeroInt int

var zeroFloat float64

var zeroString string

var zeroBool bool

fmt.Printf("Zero int: %d\n", zeroInt)

fmt.Printf("Zero float: %f\n", zeroFloat)

fmt.Printf("Zero string: %s\n", zeroString)

fmt.Printf("Zero bool: %t\n", zeroBool)

}

A variable’s type determines the value allocated to it when it is defined but not explicitly initialised. These examples address a variety of topics related to using variables in Go. You will have a better grasp of how variables work in Go programmes by experimenting with these ideas.

Strings in Golang

Double quotes ("...") are used in Go to express a string as a succession of characters. Go handles strings as immutable, which means that once a string is formed, it is impossible to modify its contents. The following are some essential components of using strings in Golang, along with illustrations:

Declaring and Initializing Strings

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Declaring and initializing a string

greeting := "Hello, Golang!"

fmt.Println(greeting)

}

In this example, the variable greeting is declared and initialized with the string “Hello, Golang!” using the short variable declaration (:=) syntax.

String Length

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

message := "Hello, World!"

// Calculating string length

length := len(message)

fmt.Printf("Length of the string: %d\n", length)

}

The len() function is used to calculate the length of a string in terms of the number of bytes.

Concatenating Strings

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

firstName := "John"

lastName := "Doe"

// Concatenating strings

fullName := firstName + " " + lastName

fmt.Println("Full Name:", fullName)

}

Strings can be concatenated using the + operator.

String Indexing and Slicing

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

message := "Hello, Gophers!"

// Accessing individual characters (byte-wise)

firstChar := message[0]

fmt.Println("First Character:", string(firstChar))

// Slicing a string

slicedString := message[7:15]

fmt.Println("Sliced String:", slicedString)

}

In Go, strings are made up of bytes. You can access individual characters by indexing the string. Also, you can create a substring (sliced string) using the slice notation.

String Formatting

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

name := "Alice"

age := 25

// String formatting using Printf

message := fmt.Sprintf("Name: %s, Age: %d", name, age)

fmt.Println(message)

}

The fmt.Sprintf function is used for string formatting. It returns a formatted string without printing it to the console.

Unicode Support

Go has excellent support for Unicode characters in strings, allowing you to work with a wide range of international characters.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

unicodeString := "こんにちは, 世界!" // Hello, World! in Japanese

fmt.Println(unicodeString)

}

The Japanese phrase “Hello, World!” is represented by Unicode characters in the given string.

Some of the fundamental procedures and ideas associated with working with strings in Go are covered in these examples. You will be able to manage and deal with strings in your Go programmes more efficiently if you grasp these foundations.

Arrays in Golang

An array in Go is a fixed-size grouping of identically typed items. An array’s size cannot be altered once it has been constructed. An overview of declaring, initialising, and using arrays in Golang is provided here:

Declaring and Initializing Arrays

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Declaration and initialization of an array

var numbers [5]int // An array of integers with a size of 5

numbers = [5]int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5} // Initializing array elements individually

moreNumbers := [5]int{6, 7, 8, 9, 10} // Short declaration with initialization

fmt.Println("Numbers:", numbers)

fmt.Println("More Numbers:", moreNumbers)

}

In this example, we declare and initialize an array called numbers with a size of 5. The elements are then assigned individually. The short declaration syntax is used for another array called moreNumbers.

Accessing Array Elements

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

numbers := [5]int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

// Accessing array elements

firstElement := numbers[0]

thirdElement := numbers[2]

fmt.Println("First Element:", firstElement)

fmt.Println("Third Element:", thirdElement)

}

Array elements can be accessed using their index. The index starts from 0.

Array Length

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

numbers := [5]int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

// Getting the length of the array

length := len(numbers)

fmt.Println("Length of the array:", length)

}

The len() function can be used to get the length (number of elements) of an array.

Iterating Over Arrays

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

numbers := [5]int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

// Iterating over array elements

for index, value := range numbers {

fmt.Printf("Index: %d, Value: %d\n", index, value)

}

}

The range keyword is used to iterate over the elements of an array, providing both the index and value at each iteration.

Multidimensional Arrays

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Declaration and initialization of a 2D array

var matrix [3][3]int

matrix = [3][3]int{

{1, 2, 3},

{4, 5, 6},

{7, 8, 9},

}

fmt.Println("Matrix:", matrix)

}

There are multidimensional arrays as well. A 2D array (matrix) is declared and initialised in this example.

Writing clear and simple code in Go requires knowing how to work with arrays, which are a basic data structure. Remember that slices offer a more adaptable substitute for arrays in situations where dynamic scaling is necessary.

Slices in Golang

A slice is a flexible, dynamically-sized view into an array’s elements in Go. Compared to arrays, slices are more potent and adaptable because of their ability to dynamically alter size during runtime. An overview of declaring, creating, and working with slices in Golang is provided here:

Declaring and Creating Slices

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Declaration and creation of a slice

var numbers []int // Declaration of an integer slice

numbers = []int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5} // Initialization of the slice

moreNumbers := []int{6, 7, 8, 9, 10} // Short declaration with initialization

fmt.Println("Numbers:", numbers)

fmt.Println("More Numbers:", moreNumbers)

}

In this example, we declare and initialize a slice called numbers. The size of a slice is not specified in the declaration, and it is determined by the number of elements provided during initialization.

Accessing and Modifying Slice Elements

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

numbers := []int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

// Accessing and modifying slice elements

firstElement := numbers[0]

thirdElement := numbers[2]

fmt.Println("First Element:", firstElement)

numbers[1] = 20 // Modifying the second element

fmt.Println("Modified Slice:", numbers)

}

Similar to arrays, you can access and modify elements of a slice using their index.

Slicing Slices

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

numbers := []int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

// Slicing a slice

slicedNumbers := numbers[1:4]

fmt.Println("Sliced Numbers:", slicedNumbers)

}

Slices support a “slicing” operation to create a new slice from a subset of the original slice.

Appending to Slices

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

numbers := []int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

// Appending elements to a slice

numbers = append(numbers, 6, 7, 8)

fmt.Println("Updated Slice:", numbers)

}

The append function is used to add elements to the end of a slice. If the underlying array is not large enough to accommodate the new elements, a new array is allocated, and the existing elements are copied.

Length and Capacity of Slices

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

numbers := []int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

// Length of the slice

length := len(numbers)

// Capacity of the slice

capacity := cap(numbers)

fmt.Printf("Length: %d, Capacity: %d\n", length, capacity)

}

The len() function returns the length (number of elements) of a slice, while the cap() function returns the capacity (maximum number of elements it can hold without resizing).

Copying Slices

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

numbers := []int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

anotherNumbers := make([]int, len(numbers))

// Copying elements from one slice to another

copy(anotherNumbers, numbers)

fmt.Println("Copied Slice:", anotherNumbers)

}

To copy items from one slice to another, use the copy function. It is necessary to build the destination slice with sufficient capacity to hold the copied components.

Go’s Slices data structure is strong and adaptable, allowing for the effective and dynamic manipulation of collections. Writing clear and effective Go code requires knowing how to interact with slices.

Maps in Golang

A map in the Go language is an array of key-value pairs where every key has to be distinct. Because they are dynamic and unordered, maps make for quick and easy lookups and changes. An overview of declaring, creating, and using maps in Golang is provided here:

Declaring and Creating Maps

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Declaration and creation of a map

var colors map[string]string // Declaration of a map with string keys and string values

colors = make(map[string]string) // Creating an empty map

colors["red"] = "#ff0000" // Adding key-value pairs to the map

colors["green"] = "#00ff00"

colors["blue"] = "#0000ff"

fmt.Println("Colors:", colors)

}

In this example, we declare and create a map called colors with string keys and string values. The make function is used to create an empty map, and key-value pairs are added using the square bracket notation.

Accessing and Modifying Map Elements

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

colors := make(map[string]string)

// Adding key-value pairs

colors["red"] = "#ff0000"

colors["green"] = "#00ff00"

colors["blue"] = "#0000ff"

// Accessing and modifying map elements

redHex := colors["red"]

colors["green"] = "#008000"

fmt.Println("Red Hex:", redHex)

fmt.Println("Updated Colors:", colors)

}

Map elements can be accessed and modified using the key in square brackets.

Deleting Map Elements

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

colors := map[string]string{

"red": "#ff0000",

"green": "#00ff00",

"blue": "#0000ff",

}

// Deleting map elements

delete(colors, "green")

fmt.Println("Updated Colors:", colors)

}

The delete function is used to remove a key-value pair from the map.

Checking for Existence

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

colors := map[string]string{

"red": "#ff0000",

"green": "#00ff00",

"blue": "#0000ff",

}

// Checking for the existence of a key

if value, exists := colors["green"]; exists {

fmt.Println("Green Hex:", value)

} else {

fmt.Println("Green key does not exist.")

}

}

When checking for the existence of a key, the second return value from the map lookup indicates whether the key exists.

Iterating Over Maps

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

colors := map[string]string{

"red": "#ff0000",

"green": "#00ff00",

"blue": "#0000ff",

}

// Iterating over map elements

for key, value := range colors {

fmt.Printf("Key: %s, Value: %s\n", key, value)

}

}

The range keyword is used to iterate over the key-value pairs in a map.

Maps with Non-String Keys

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Map with non-string keys

ages := map[string]int{

"Alice": 25,

"Bob": 30,

"Charlie": 35,

}

fmt.Println("Ages:", ages)

}

Although strings are frequently used as keys, Go allows keys of any similar kind for maps as well.

In Go, maps are a strong and adaptable data structure that may be used in a variety of scenarios. Writing clear and simple Go code requires an understanding of how to interact with maps.

Loops in Golang

The for loop is the sole kind of loop that exists in Go. Nonetheless, the for loop exhibits great flexibility and may be employed to accomplish diverse looping behaviours. Here are some Golang examples of loop usage:

Basic for Loop

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Basic for loop

for i := 0; i < 5; i++ {

fmt.Println(i)

}

}

In this example, a basic for loop is used to print numbers from 0 to 4.

for Loop with a Condition

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// For loop with a condition

counter := 0

for counter < 5 {

fmt.Println(counter)

counter++

}

}

You can use a for loop with just a condition, similar to a while loop in other languages.

Infinite Loop

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Infinite loop

i := 0

for {

fmt.Println(i)

i++

if i == 5 {

break // Exit the loop when i equals 5

}

}

}

By omitting the loop condition entirely, you create an infinite loop. You can use the break statement to exit the loop when a certain condition is met.

for Loop with Range

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// For loop with range (used for iterating over slices, arrays, maps, etc.)

numbers := []int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

for index, value := range numbers {

fmt.Printf("Index: %d, Value: %d\n", index, value)

}

}

The range keyword is used in a for loop to iterate over elements in slices, arrays, maps, and other data structures.

Nested for Loop

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Nested for loop

for i := 0; i < 3; i++ {

for j := 0; j < 2; j++ {

fmt.Printf("i: %d, j: %d\n", i, j)

}

}

}

You can nest for loops to achieve multiple levels of iteration.

Loop Control Statements: break and continue

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Loop control statements: break and continue

for i := 0; i < 5; i++ {

if i == 2 {

continue // Skip the current iteration when i equals 2

}

fmt.Println(i)

if i == 3 {

break // Exit the loop when i equals 3

}

}

}

The loop may be broken with the break statement, and the remaining iteration can be skipped to go on to the next one with the continue statement.

These examples cover a variety of `for} loop use scenarios in Go. You can develop more expressive and effective loop structures in your Go programmes if you grasp these ideas.

Condition in Golang

The if, else if, and else phrases are used in Go to express conditionals. Here are some Golang instances of conditionals in use:

if Statement

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Simple if statement

age := 25

if age >= 18 {

fmt.Println("You are eligible to vote.")

}

}

In this example, the if statement checks if the age is greater than or equal to 18, and if true, it prints a message.

if with Short Statement

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// If statement with a short statement

if age := 25; age >= 18 {

fmt.Println("You are eligible to vote.")

}

}

You can initialize a variable in the if statement itself, and its scope will be limited to that block.

if and else

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// If-else statement

age := 15

if age >= 18 {

fmt.Println("You are eligible to vote.")

} else {

fmt.Println("You are not eligible to vote yet.")

}

}

Here, the else block is executed if the condition in the if statement is false.

if with else if

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// If-else if-else statement

score := 85

if score >= 90 {

fmt.Println("A")

} else if score >= 80 {

fmt.Println("B")

} else if score >= 70 {

fmt.Println("C")

} else {

fmt.Println("D")

}

}

You can use multiple else if statements to handle multiple conditions.

Switch Statement

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Switch statement

day := "Monday"

switch day {

case "Monday":

fmt.Println("It's the start of the week.")

case "Friday":

fmt.Println("It's almost the weekend.")

default:

fmt.Println("It's a regular day.")

}

}

The switch statement is used for multiple branches based on the value of an expression.

switch with No Expression

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Switch statement with no expression

today := "Sunday"

switch {

case today == "Saturday" || today == "Sunday":

fmt.Println("It's the weekend!")

default:

fmt.Println("It's a weekday.")

}

}

A switch statement without an expression can be used as an alternative to a long if-else if-else chain.

These examples demonstrate the use of conditionals in Go. Understanding how to use if, else, and switch statements allows you to make decisions and control the flow of your Go programs effectively.

Operators in Go

Operators in Go are symbols that operate on operands. An outline of the most prevalent operator types in Go is provided below:

Arithmetic Operators

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Arithmetic operators

a := 10

b := 3

fmt.Println("Addition:", a+b)

fmt.Println("Subtraction:", a-b)

fmt.Println("Multiplication:", a*b)

fmt.Println("Division:", a/b)

fmt.Println("Remainder:", a%b)

fmt.Println("Increment:", a+1)

fmt.Println("Decrement:", a-1)

}

+Addition-Subtraction*Multiplication/Division%Remainder (Modulus)++Increment--Decrement

Relational Operators

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Relational operators

x := 5

y := 8

fmt.Println("Equal:", x == y)

fmt.Println("Not Equal:", x != y)

fmt.Println("Greater Than:", x > y)

fmt.Println("Less Than:", x < y)

fmt.Println("Greater Than or Equal To:", x >= y)

fmt.Println("Less Than or Equal To:", x <= y)

}

==Equal to!=Not equal to>Greater than<Less than>=Greater than or equal to<=Less than or equal to

Logical Operators

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Logical operators

isTrue := true

isFalse := false

fmt.Println("AND:", isTrue && isFalse)

fmt.Println("OR:", isTrue || isFalse)

fmt.Println("NOT:", !isTrue)

}

&&Logical AND||Logical OR!Logical NOT

Assignment Operators

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Assignment operators

a := 10

b := 5

a += b // Equivalent to a = a + b

fmt.Println("a:", a)

a -= b // Equivalent to a = a - b

fmt.Println("a:", a)

a *= b // Equivalent to a = a * b

fmt.Println("a:", a)

a /= b // Equivalent to a = a / b

fmt.Println("a:", a)

a %= b // Equivalent to a = a % b

fmt.Println("a:", a)

}

+=Addition assignment-=Subtraction assignment*=Multiplication assignment/=Division assignment%=Remainder assignment

Bitwise Operators

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Bitwise operators

a := 5

b := 3

fmt.Println("AND:", a&b)

fmt.Println("OR:", a|b)

fmt.Println("XOR:", a^b)

fmt.Println("AND NOT:", a&^b)

fmt.Println("Left Shift:", a<<1)

fmt.Println("Right Shift:", a>>1)

}

&Bitwise AND|Bitwise OR^Bitwise XOR&^Bitwise AND NOT<<Left shift>>Right shift

In Go, these are the most frequently used operators. Writing efficient and clear Go code requires knowing how to utilise these operators.

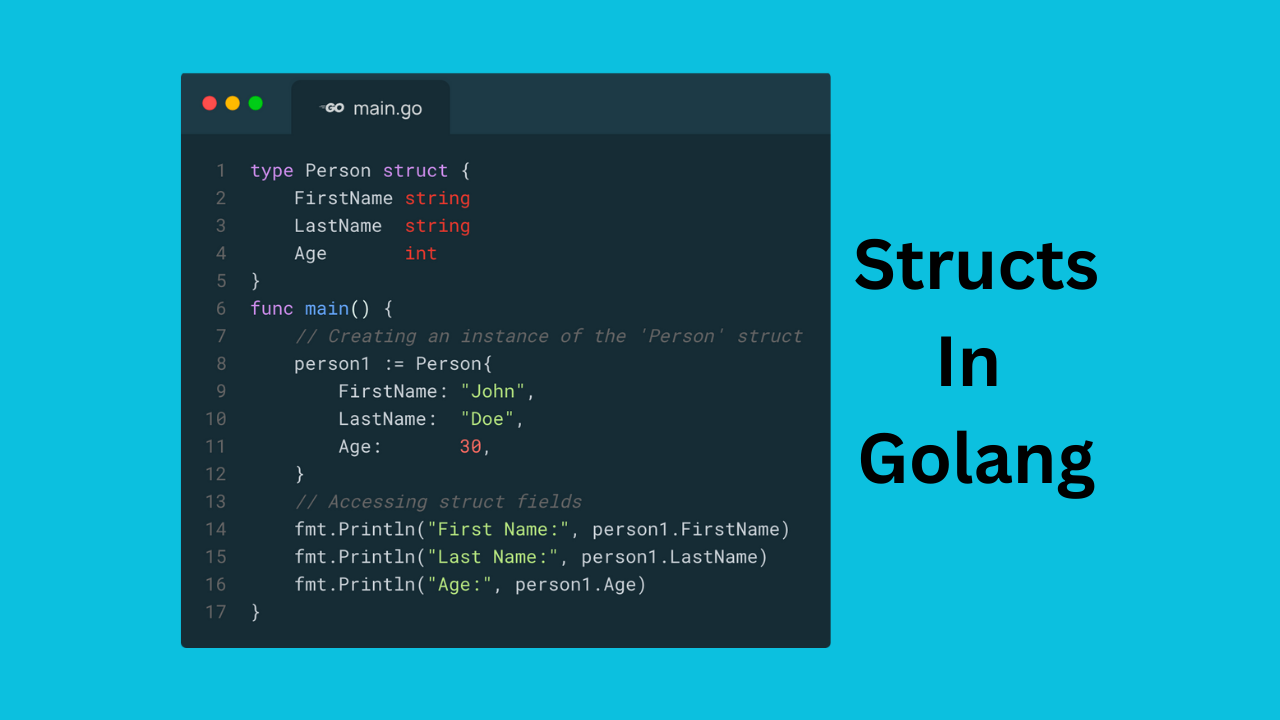

Structs in Golang

A struct is a composite data type in Go that unifies variables, also known as fields, under a single name. A struct’s fields may each have a distinct data type. Using structures, you may design user-defined types that group and encapsulate similar data points. An overview of Go’s struct definition and usage can be found here:

Defining a Struct

package main

import "fmt"

// Defining a struct named 'Person'

type Person struct {

FirstName string

LastName string

Age int

}

func main() {

// Creating an instance of the 'Person' struct

person1 := Person{

FirstName: "John",

LastName: "Doe",

Age: 30,

}

// Accessing struct fields

fmt.Println("First Name:", person1.FirstName)

fmt.Println("Last Name:", person1.LastName)

fmt.Println("Age:", person1.Age)

}

In this example, a struct named Person is defined with three fields: FirstName, LastName, and Age. An instance of this struct is created with specific values, and the fields are accessed using dot notation.

Anonymous Structs

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Creating an anonymous struct

person := struct {

FirstName string

LastName string

Age int

}{

FirstName: "Alice",

LastName: "Smith",

Age: 25,

}

fmt.Println("First Name:", person.FirstName)

fmt.Println("Last Name:", person.LastName)

fmt.Println("Age:", person.Age)

}

Anonymous structs are structs defined without a specified name. They are useful for creating one-time-use data structures.

Struct Embedding (Composition)

package main

import "fmt"

// Defining a 'Contact' struct

type Contact struct {

Email string

Phone string

}

// Defining a 'Person' struct with embedded 'Contact'

type Person struct {

FirstName string

LastName string

Age int

Contact // Embedding the 'Contact' struct

}

func main() {

// Creating an instance of the 'Person' struct with embedded 'Contact'

person := Person{

FirstName: "Bob",

LastName: "Johnson",

Age: 35,

Contact: Contact{

Email: "bob@example.com",

Phone: "555-1234",

},

}

fmt.Println("First Name:", person.FirstName)

fmt.Println("Last Name:", person.LastName)

fmt.Println("Age:", person.Age)

fmt.Println("Email:", person.Email) // Accessing embedded struct field

fmt.Println("Phone:", person.Phone) // Accessing embedded struct field

}

Struct embedding allows one struct to be embedded within another, forming a composition relationship.

Methods with Structs

package main

import "fmt"

// Defining a 'Person' struct

type Person struct {

FirstName string

LastName string

Age int

}

// Adding a method to the 'Person' struct

func (p Person) FullName() string {

return p.FirstName + " " + p.LastName

}

func main() {

// Creating an instance of the 'Person' struct

person := Person{

FirstName: "Charlie",

LastName: "Brown",

Age: 28,

}

// Calling the 'FullName' method

fullName := person.FullName()

fmt.Println("Full Name:", fullName)

}

It is possible to define methods related to structs. In this example, the Person struct now has the FullName function attached to it.

Go’s structures offer a strong and adaptable method for structuring and organising data in your programmes. They are frequently used to model real-world things and represent complicated data kinds.

Functions in Golang

Functions are code blocks in Go that carry out particular tasks. They are fundamental components of every Go programme. An overview of Golang function definition and use is provided here:

Function Declaration

package main

import "fmt"

// Function named 'sayHello'

func sayHello() {

fmt.Println("Hello, Go!")

}

func main() {

// Calling the 'sayHello' function

sayHello()

}

In this example, a function named sayHello is declared and defined. It prints “Hello, Go!” when called from the main function.

Function Parameters

package main

import "fmt"

// Function with parameters

func greet(name string) {

fmt.Printf("Hello, %s!\n", name)

}

func main() {

// Calling the 'greet' function with an argument

greet("Alice")

greet("Bob")

}

Functions can have parameters. The greet function takes a name parameter, allowing it to greet different individuals.

Multiple Parameters

package main

import "fmt"

// Function with multiple parameters

func add(a, b int) {

result := a + b

fmt.Printf("%d + %d = %d\n", a, b, result)

}

func main() {

// Calling the 'add' function with two arguments

add(3, 7)

}

Functions can have multiple parameters. The add function takes two integers as parameters and prints their sum.

Return Values

package main

import "fmt"

// Function with a return value

func multiply(a, b int) int {

return a * b

}

func main() {

// Calling the 'multiply' function and using the returned value

result := multiply(4, 5)

fmt.Println("Result:", result)

}

Functions can return values. The multiply function takes two integers as parameters and returns their product.

Named Return Values

package main

import "fmt"

// Function with named return values

func divide(a, b float64) (quotient float64, remainder float64) {

quotient = a / b

remainder = a - (quotient * b)

return

}

func main() {

// Calling the 'divide' function and using the returned values

q, r := divide(10, 3)

fmt.Printf("Quotient: %.2f, Remainder: %.2f\n", q, r)

}

You can specify named return values in the function signature. This example shows a function named divide that returns both the quotient and remainder.

Variadic Functions

package main

import "fmt"

// Variadic function (accepts a variable number of arguments)

func sum(numbers ...int) int {

total := 0

for _, num := range numbers {

total += num

}

return total

}

func main() {

// Calling the 'sum' function with a variable number of arguments

result := sum(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

fmt.Println("Sum:", result)

}

Variadic functions can accept a variable number of arguments. The sum function takes any number of integers and calculates their sum.

Anonymous Functions (Closures)

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Anonymous function (closure)

add := func(a, b int) int {

return a + b

}

// Calling the anonymous function

result := add(8, 12)

fmt.Println("Result:", result)

}

Anonymous functions, also known as closures, are functions without a name. They can be assigned to variables and used like any other function.

Function as a Parameter

package main

import "fmt"

// Function that takes another function as a parameter

func operate(a, b int, operation func(int, int) int) {

result := operation(a, b)

fmt.Println("Result:", result)

}

func main() {

// Defining an anonymous function and passing it as a parameter

add := func(a, b int) int {

return a + b

}

// Calling the 'operate' function with the 'add' function as a parameter

operate(10, 5, add)

}

One function can pass another function as a parameter. A operate function that accepts two numbers and an additional function as parameters is demonstrated in this example.

Go functions are essential building blocks that help to better organise and structure code for modularity and reusability. It is essential to know how to define, call, and manipulate functions while building Go programmes.

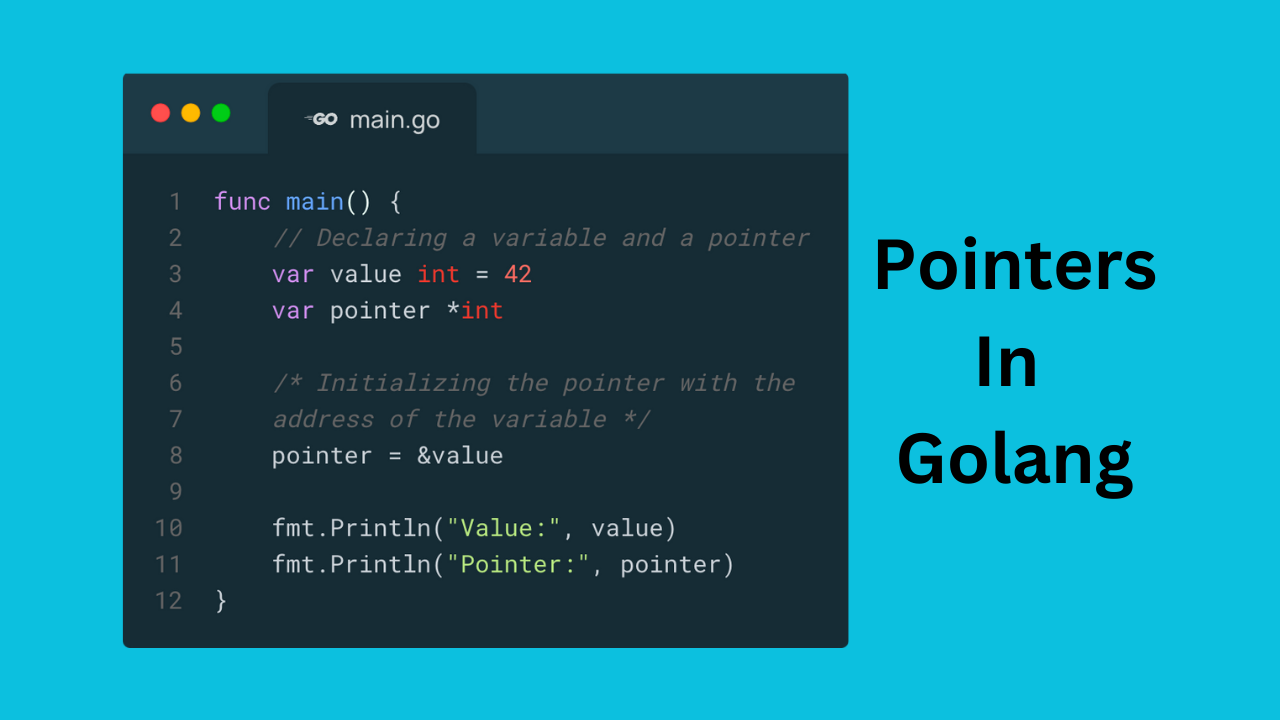

Pointers in Golang

Pointers are variables in Go that hold the address of another variable in memory. They serve as an oblique reference to the value kept in a certain memory region. This is a summary of how to use pointers in Go:

Declaring and Initializing Pointers

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Declaring a variable and a pointer

var value int = 42

var pointer *int

// Initializing the pointer with the address of the variable

pointer = &value

fmt.Println("Value:", value)

fmt.Println("Pointer:", pointer)

}

In this example, a variable value is declared, and a pointer pointer is declared. The pointer is then initialized with the address of the value variable using the & operator.

Dereferencing Pointers

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Declaring a variable and a pointer

var value int = 42

var pointer *int

// Initializing the pointer with the address of the variable

pointer = &value

// Dereferencing the pointer to get the value it points to

dereferencedValue := *pointer

fmt.Println("Value:", value)

fmt.Println("Dereferenced Value:", dereferencedValue)

}

The * operator is used to dereference a pointer, which means accessing the value stored at the memory address held by the pointer.

Modifying Variable through Pointers

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Declaring a variable and a pointer

var value int = 42

var pointer *int

// Initializing the pointer with the address of the variable

pointer = &value

// Modifying the variable through the pointer

*pointer = 100

fmt.Println("Modified Value:", value)

}

Since the pointer holds the memory address of a variable, modifying the value through the pointer also modifies the original variable.

Nil Pointers

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Declaring a nil pointer

var pointer *int

// Checking if the pointer is nil

if pointer == nil {

fmt.Println("Pointer is nil")

} else {

fmt.Println("Pointer is not nil")

}

}

A pointer that is not assigned any memory address is called a “nil” pointer. It is the zero value for pointers in Go.

New Function

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Using the 'new' function to create a pointer

pointer := new(int)

// Assigning a value through the pointer

*pointer = 42

fmt.Println("Value assigned through 'new' pointer:", *pointer)

}

The new function is used to create a new variable and return its memory address as a pointer.

Pointers with Structs

package main

import "fmt"

// Defining a struct

type Person struct {

FirstName string

LastName string

Age int

}

func main() {

// Creating an instance of the struct

person := Person{

FirstName: "John",

LastName: "Doe",

Age: 30,

}

// Creating a pointer to the struct

var pointer *Person

pointer = &person

// Accessing struct fields through the pointer

fmt.Println("First Name:", pointer.FirstName)

fmt.Println("Last Name:", pointer.LastName)

fmt.Println("Age:", pointer.Age)

}

A struct’s fields can be accessed and changed via pointers. In this example, the fields of a `Person} struct are accessed by creating a reference to the struct.

Go’s pointers let you directly manage and alter memory, giving you more control over how your programmes behave. Comprehending the usage of pointers is essential for advancing programming assignments and effective memory management in Go.

Methods in Golang

Methods in Go are functions connected to a certain type. They let you specify actions or behaviours unique to instances of a particular kind. An outline of how to define and utilise methods in Go is provided below:

Method Declaration

package main

import "fmt"

// Defining a struct type

type Rectangle struct {

Width float64

Height float64

}

// Method associated with the Rectangle type

func (r Rectangle) Area() float64 {

return r.Width * r.Height

}

func main() {

// Creating an instance of the Rectangle struct

rectangle := Rectangle{Width: 5, Height: 10}

// Calling the method on the struct instance

area := rectangle.Area()

fmt.Println("Area:", area)

}

In this example, a method named Area is associated with the Rectangle type. The method is called on an instance of the Rectangle struct.

Pointer Receivers

package main

import "fmt"

// Defining a struct type

type Rectangle struct {

Width float64

Height float64

}

// Method with a pointer receiver

func (r *Rectangle) Scale(factor float64) {

r.Width *= factor

r.Height *= factor

}

func main() {

// Creating an instance of the Rectangle struct

rectangle := Rectangle{Width: 5, Height: 10}

// Calling the method with a pointer receiver

rectangle.Scale(2)

fmt.Printf("Width: %.2f, Height: %.2f\n", rectangle.Width, rectangle.Height)

}

When a method has a pointer receiver, it can modify the values of the fields in the struct directly. In this example, the Scale method modifies the width and height of the Rectangle struct.

Value Receivers vs. Pointer Receivers

The question of whether you wish to change the original value determines whether to use a value receiver or a pointer receiver.

- Use a value receiver if the method does not modify the original value.

- Use a pointer receiver if the method needs to modify the original value.

Methods with Pointers as Parameters

package main

import "fmt"

// Defining a struct type

type Point struct {

X float64

Y float64

}

// Method with a pointer receiver and a pointer parameter

func (p *Point) MoveTo(newX, newY float64) {

p.X = newX

p.Y = newY

}

func main() {

// Creating an instance of the Point struct

point := Point{X: 3, Y: 7}

// Calling the method with a pointer receiver and a pointer parameter

point.MoveTo(10, 20)

fmt.Printf("New X: %.2f, New Y: %.2f\n", point.X, point.Y)

}

Methods can also take pointers as parameters, allowing them to operate on different instances of the same type.

Methods with Named Return Values

package main

import "fmt"

// Defining a struct type

type Circle struct {

Radius float64

}

// Method with named return values

func (c Circle) DiameterAndCircumference() (diameter, circumference float64) {

diameter = 2 * c.Radius

circumference = 2 * 3.14 * c.Radius

return

}

func main() {

// Creating an instance of the Circle struct

circle := Circle{Radius: 5}

// Calling the method with named return values

diameter, circumference := circle.DiameterAndCircumference()

fmt.Printf("Diameter: %.2f, Circumference: %.2f\n", diameter, circumference)

}

It is possible for methods to have named return values, which improves readability of the code and lets you utilise those names directly when returning values.

Go methods let you create actions linked to certain types, which improves code encapsulation and expressiveness. It’s essential to grasp procedures if you want to write efficient, organised Go programmes.

Interfaces in Golang

Interfaces are a strong and adaptable method of defining contracts for behaviour in Go. Any type that implements these methods inherently fulfils the interface, which provides a set of method signatures. An overview of Go interface functionality is provided here:

Defining an Interface

package main

import "fmt"

// Defining an interface named 'Shape'

type Shape interface {

Area() float64

Perimeter() float64

}

// Defining a struct named 'Rectangle'

type Rectangle struct {

Width float64

Height float64

}

// Implementing the 'Shape' interface for 'Rectangle'

func (r Rectangle) Area() float64 {

return r.Width * r.Height

}

func (r Rectangle) Perimeter() float64 {

return 2*r.Width + 2*r.Height

}

func main() {

// Creating an instance of the 'Rectangle' struct

rectangle := Rectangle{Width: 5, Height: 10}

// Using the 'Shape' interface

var shape Shape

shape = rectangle

// Calling methods defined by the 'Shape' interface

area := shape.Area()

perimeter := shape.Perimeter()

fmt.Printf("Area: %.2f, Perimeter: %.2f\n", area, perimeter)

}

In this example, the Shape interface is defined with two methods: Area and Perimeter. The Rectangle struct implements these methods, making it implicitly satisfy the Shape interface.

Interface with Multiple Implementations

package main

import "fmt"

// Defining an interface named 'Animal'

type Animal interface {

Speak() string

}

// Implementing the 'Animal' interface for 'Dog'

type Dog struct{}

func (d Dog) Speak() string {

return "Woof!"

}

// Implementing the 'Animal' interface for 'Cat'

type Cat struct{}

func (c Cat) Speak() string {

return "Meow!"

}

func main() {

// Creating instances of 'Dog' and 'Cat'

dog := Dog{}

cat := Cat{}

// Using the 'Animal' interface with different implementations

var animal Animal

animal = dog

fmt.Println("Dog says:", animal.Speak())

animal = cat

fmt.Println("Cat says:", animal.Speak())

}

In this example, the Animal interface is implemented by both the Dog and Cat types. This demonstrates that different types can satisfy the same interface.

Empty Interface

The empty interface, denoted as interface{}, has zero methods and is satisfied by any type. It is often used when you want to work with values of different types without knowing their specific types.

package main

import "fmt"

func printValue(value interface{}) {

fmt.Println("Value:", value)

}

func main() {

// Using the empty interface

printValue(42)

printValue("Hello, Go!")

printValue(3.14)

}

Type Assertion

Type assertion is used to extract the underlying value of an interface. It checks the dynamic type of the interface value.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

var value interface{} = "Hello, Go!"

// Type assertion to get the underlying string value

stringValue, ok := value.(string)

if ok {

fmt.Println("String Value:", stringValue)

} else {

fmt.Println("Not a string!")

}

}

Type Switch

A type switch is a switch statement specifically designed for type assertions.

package main

import "fmt"

func printType(value interface{}) {

switch valueType := value.(type) {

case int:

fmt.Println("Type: int, Value:", valueType)

case string:

fmt.Println("Type: string, Value:", valueType)

default:

fmt.Println("Unknown Type!")

}

}

func main() {

// Using a type switch

printType(42)

printType("Hello, Go!")

printType(3.14)

}

Interfaces in Go provide a way to define flexible and reusable code by specifying behaviour contracts. They are a key feature for achieving polymorphism and decoupling in Go programs.